The Life and Times of Thomas

(as told by Margaret and Carla)

The Early Years

Conceived on a Botany lab table in Nairobi, Kenya in August 1974, Nkondo Thomas Nikundiwe made his grand entrance, hurtling head-first into the world on May 15, 1975. At two weeks past his due date, Nkondo gave us an early indication of his tendency toward procrastination. His birth was the talk of the Maternity Ward at Muhimbili Medical Center, Dar es Salaam, where 10 women in various stages of labor watched, with a mixture of horror and fascination, the spectacle of a White woman giving birth to the biggest baby they had ever seen. This “giant” baby, with a mass of curly brown hair, beautiful brown eyes, and skin the color of milky tea, weighed in at 7 pounds – average size for an American newborn, but a full 2 pounds heavier than the typical Tanzanian neonate.

And so it started. He changed our lives forever that day as he would later do for so many other people he encountered on his life’s journey.

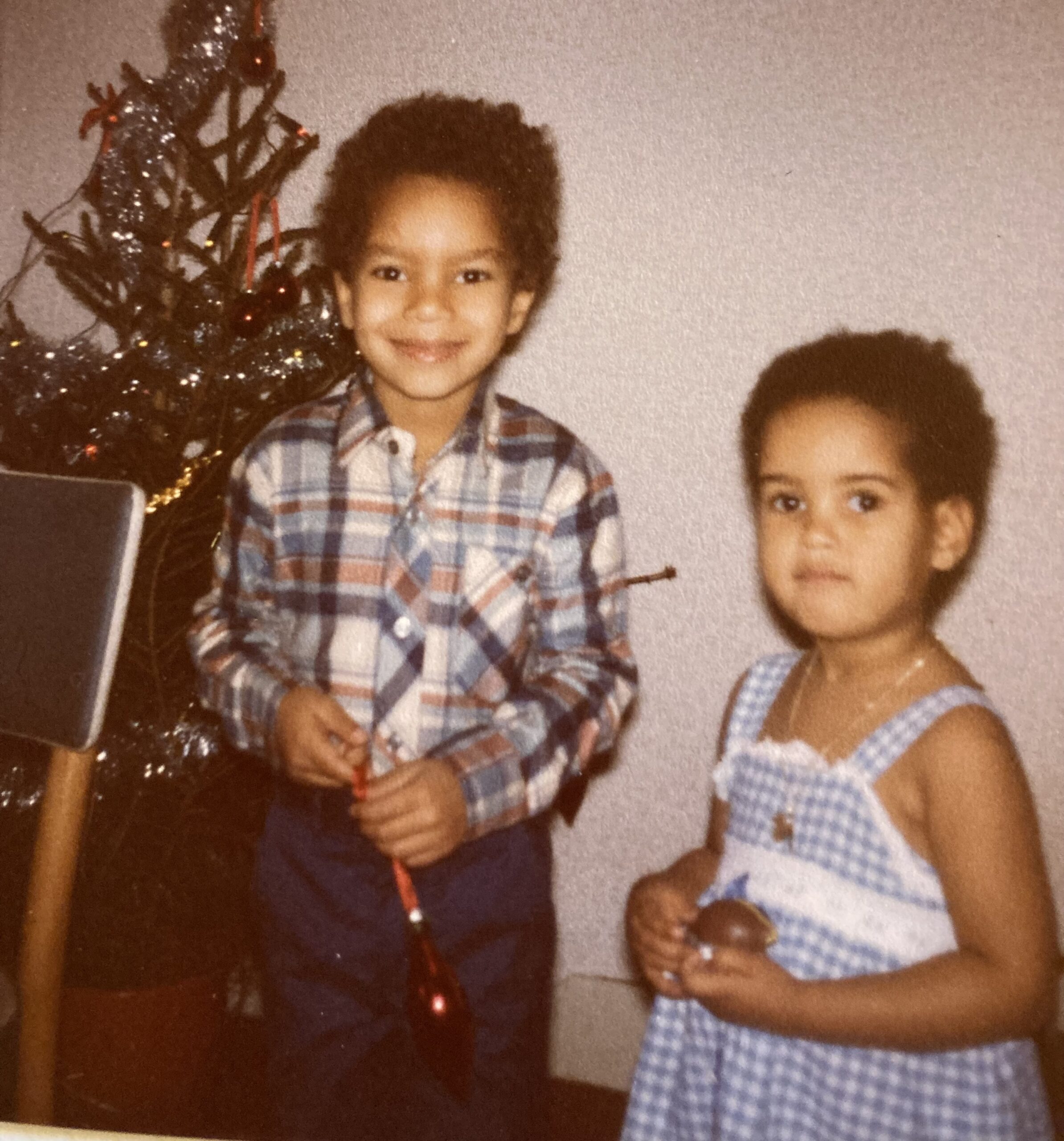

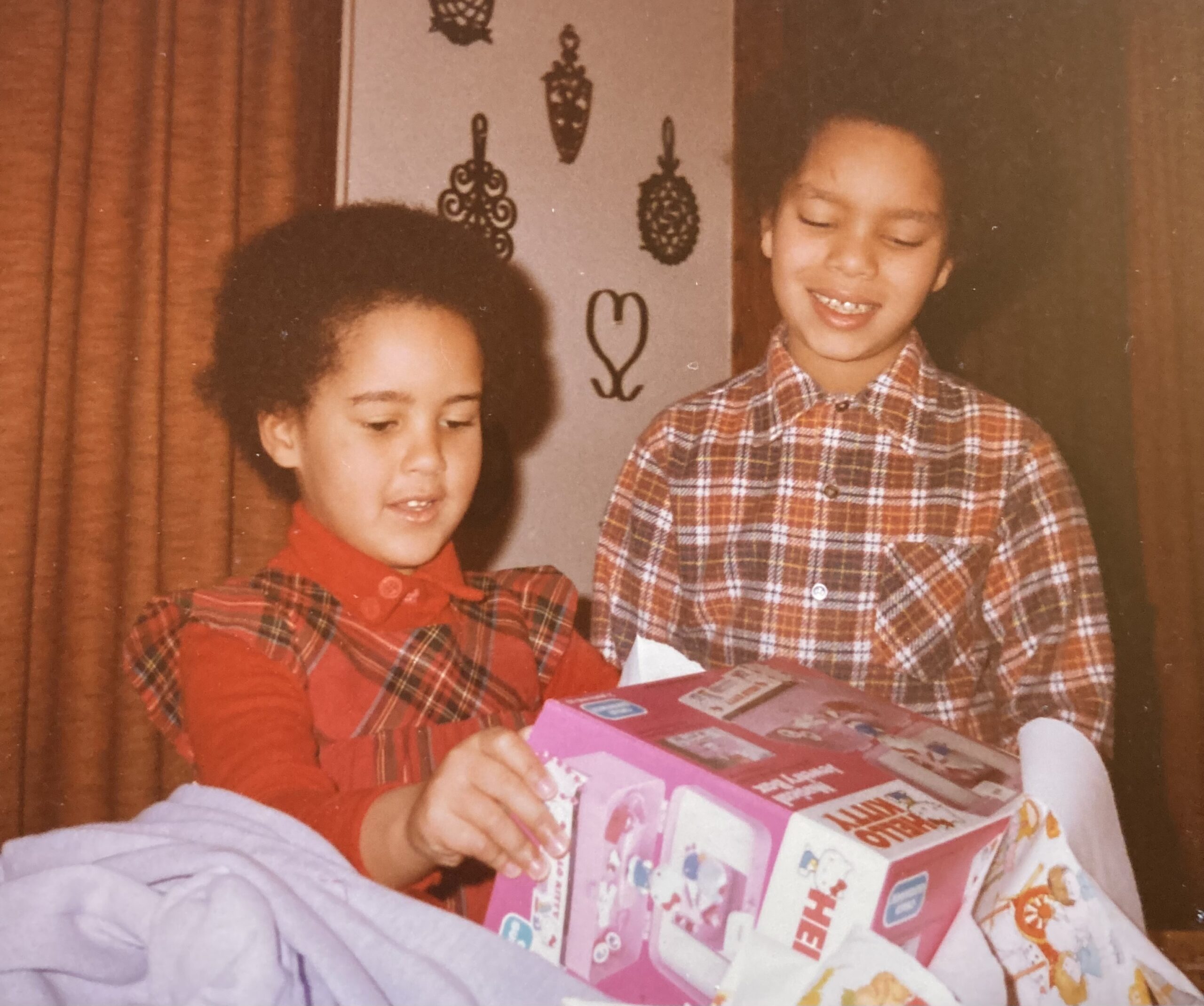

At 2 months old, Nkondo was the main attraction for a delegation of relatives visiting from the States. He was doted on by his American grandparents and tolerated by his aunts and uncle (mind you, one of the aunts and the uncle were teenagers at the time, so newborn babies weren’t really their thing). He was an early talker and a constant thinker. Photos of him as a very young child reveal a look that suggests he’s trying to figure out all of life’s mysteries, and I suspect he solved many of them before the age of 5. When he was 2 years, 8 months, his baby sister, Catherine, was born, and he immediately became her guardian, best friend, and victim, as older brothers often are of their younger sisters.

When he was 4, we visited the States for the first time to attend his grandfather’s PhD graduation and retirement celebrations. We were aboard a DC-10, a model that had been involved in several deadly accidents. Nkondo took the flight information from the pocket of the seat in front of us and said, rather loudly, “Is this a DC-10? Isn’t that the one that keeps crashing?” I don’t know how he knew that, but the other passengers looked around, startled at the troubling news coming from a 4-year-old. To everyone’s relief, we landed safely.

The Netherlands, The States, and The Newly Named Thomas Nkondo

When he was 5 1/2, we moved to The Netherlands. Three days after our arrival, he started school – a Dutch school, of course. He had never heard a word of Dutch in his life, but within a few weeks was speaking the language almost fluently and nearly flawlessly. It was then when he received his first jigsaw puzzle – a 500-piece puzzle that was the genesis of his lifelong affinity for solving puzzles. He started to put it together and got frustrated, complaining that his father – a professor and Dean of the Science Faculty – was slowing him down. He had little patience for those who would impede his progress as he sought to figure out increasingly complicated and complex conundrums, culminating in his life’s work to solve the most daunting puzzle of all: inequality and systemic racism.

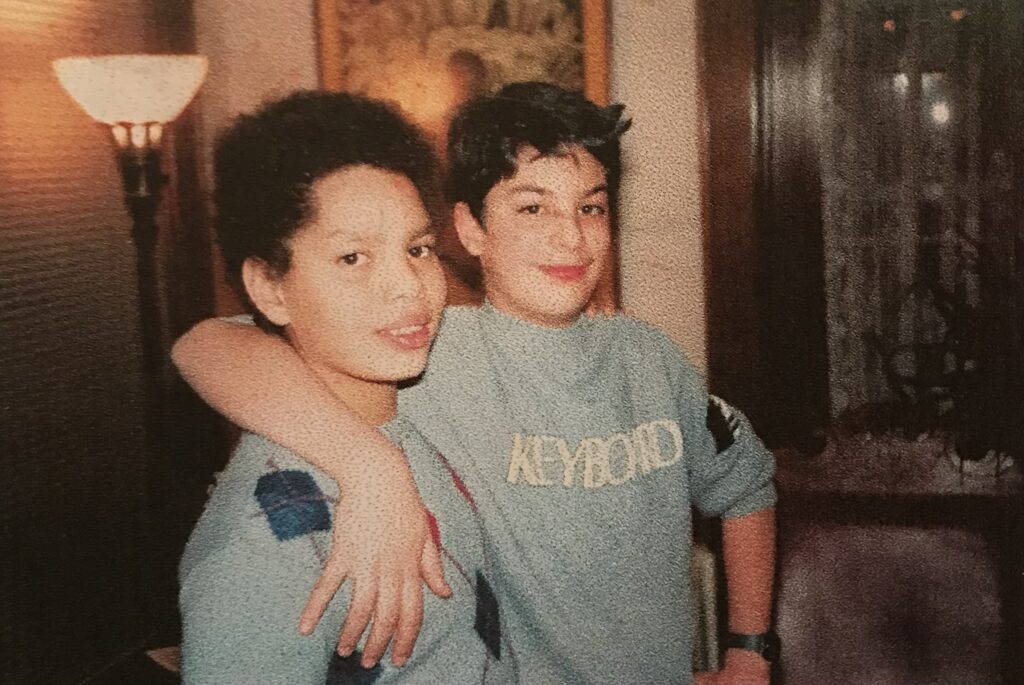

Shortly before Nkondo turned 7, his father and I split up. We stayed in the Netherlands, and his father returned to Tanzania. About a year later, we reluctantly moved to the States as immigrants – Green Card holders. The reluctance was all mine because of the racism I knew my kids would face. But they loved living in the States near their grandparents and some of their 25 or so cousins. Nkondo seemed to settle in well in his new school, making friends quickly, particularly his lifelong best friend Luke.

But, toward the end of the school year, he came to me crying, which he rarely did. He told me he was being bullied at school, mainly because of his name, though I’m sure the fact that he was an immigrant and had a pretty wild afro factored in as well. I asked him why he hadn’t told me before, and this 9-year-old boy said it was because he didn’t want to hurt my feelings because I chose his name. I explained how the naming system worked in our tribe and assured him I didn’t choose his name and had no attachment to it. I asked if he would like to switch his first and middle names around when he registers for the coming school year, and he enthusiastically replied, “Can we do it now?” I said, of course, and thus, Thomas Nkondo Nikundiwe was born on May 24, 1984.

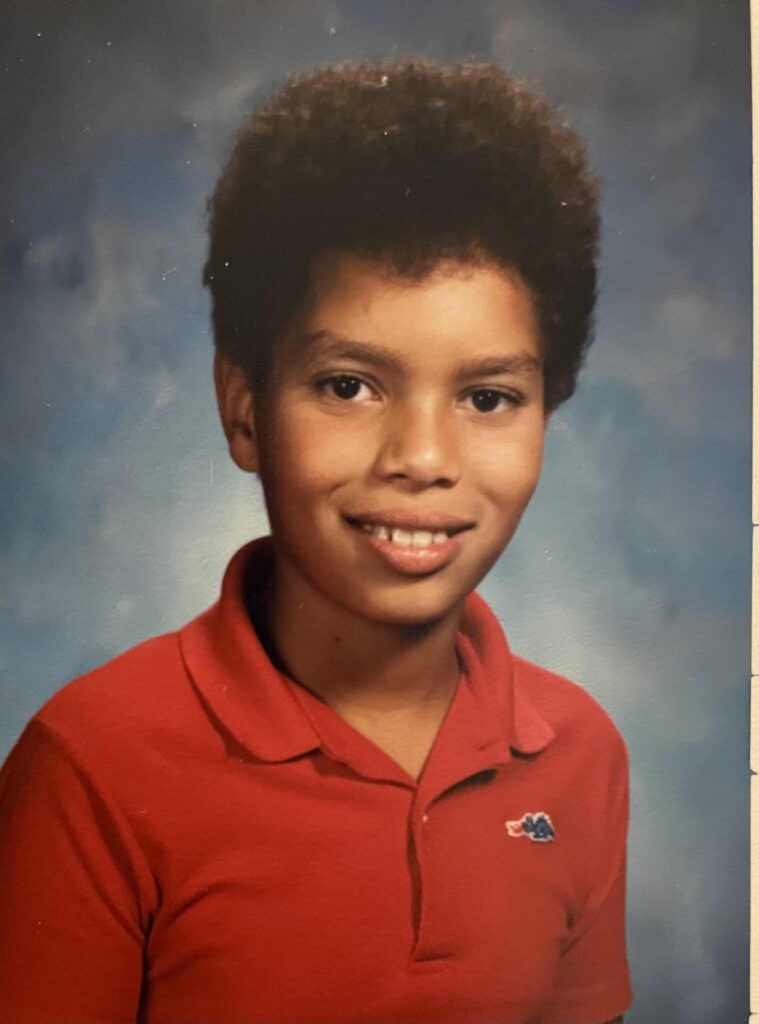

The Rest of Elementary and Middle School

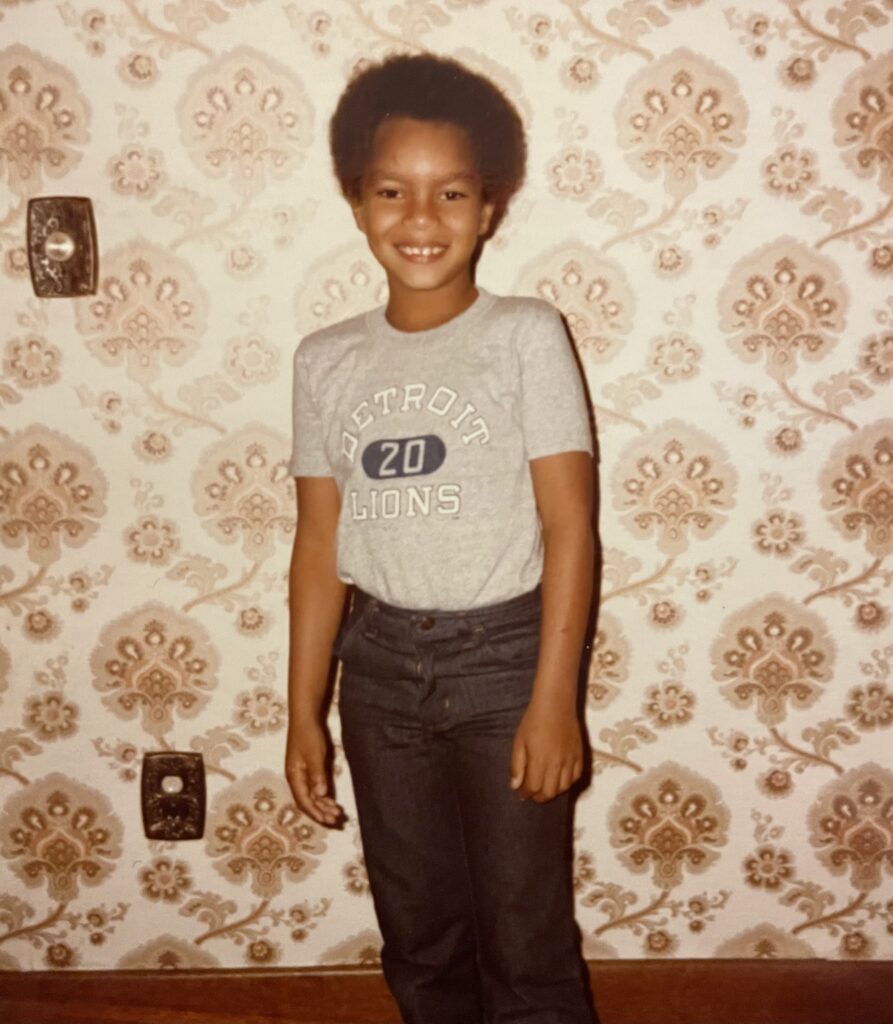

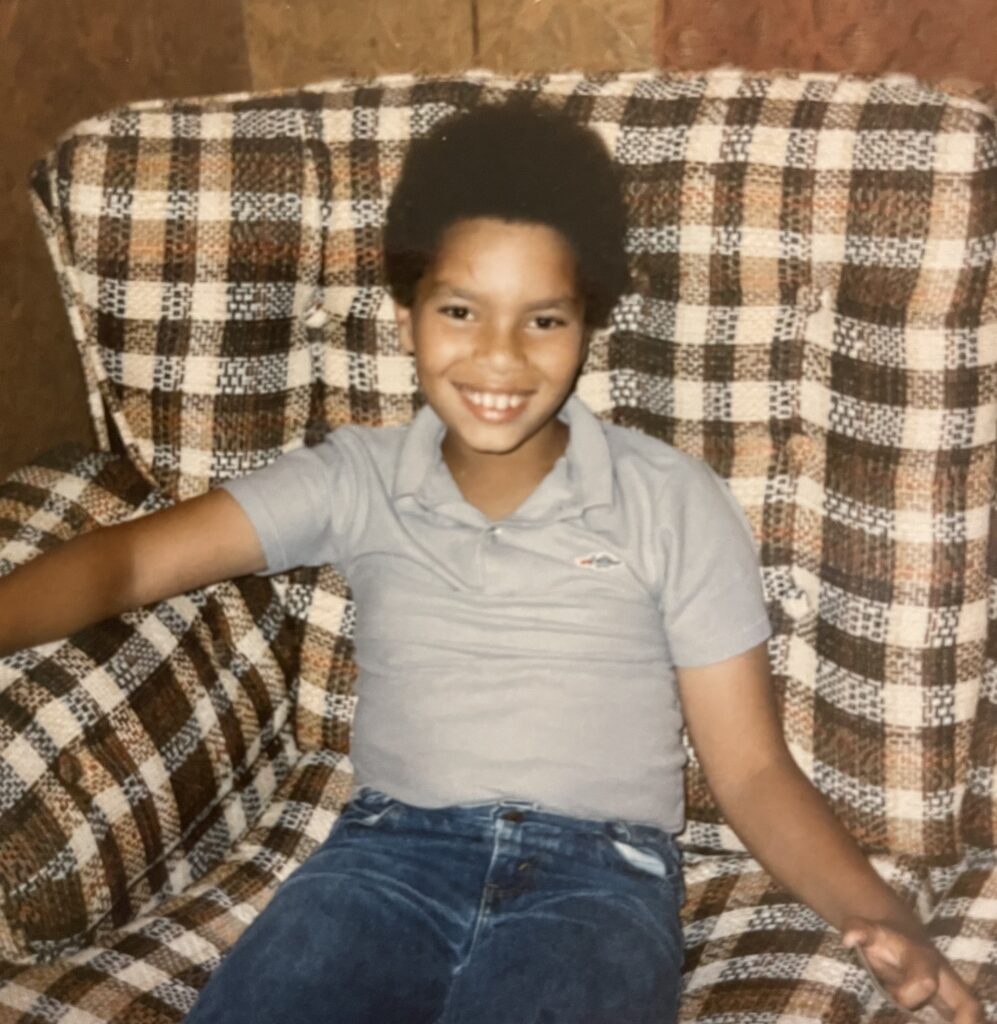

The rest of elementary school was fairly mundane. He excelled academically and socially. It was an old-fashioned neighborhood school, so all of his school friends lived nearby. Daily games of football, basketball, and soccer, depending on the season, were staples in his life and resulted in lasting friendships and a growing self-confidence.

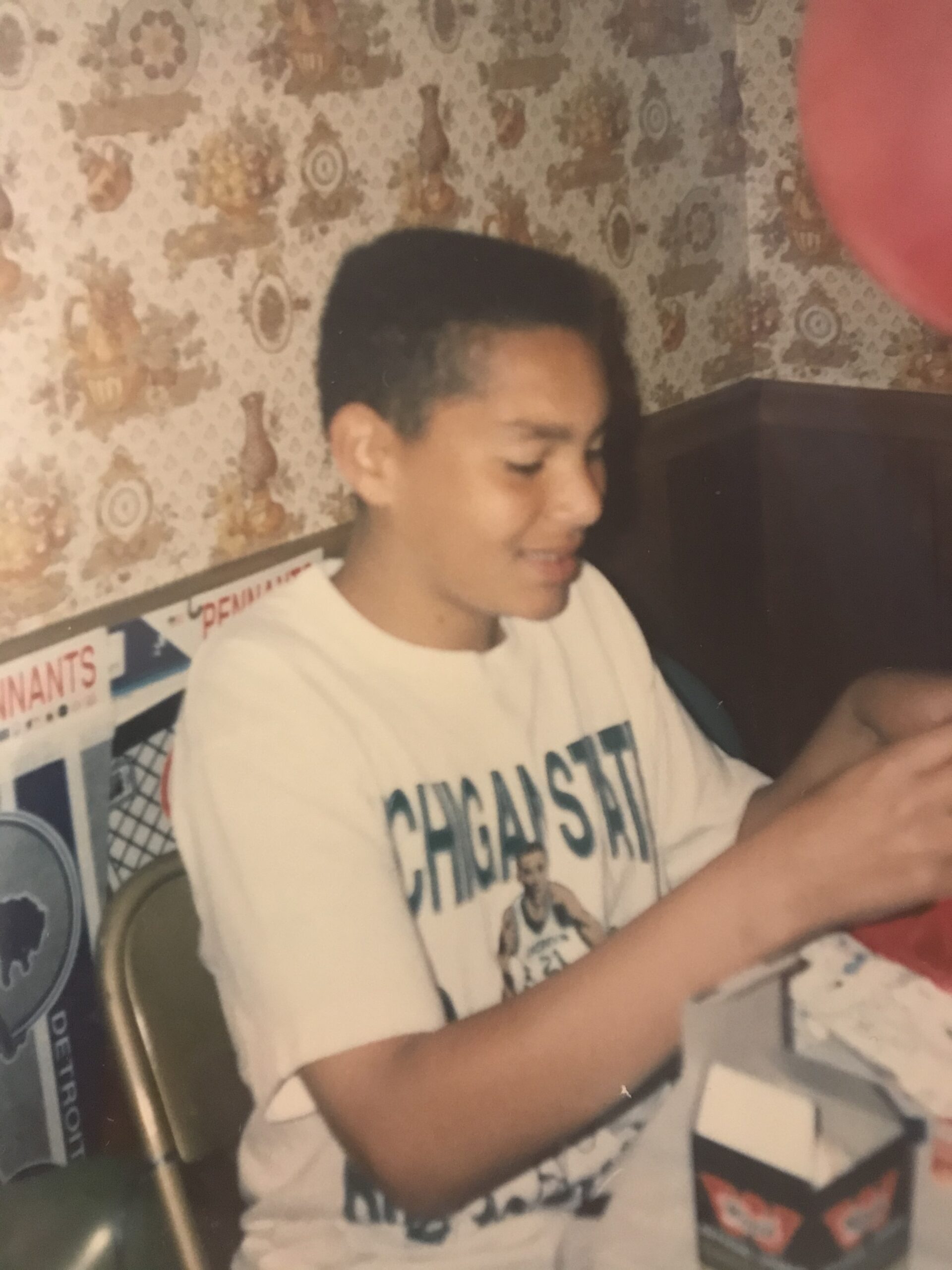

Middle school was an entirely new experience for him, as it was for all the students. Suddenly, he was met with a large number of kids from outside the safety and security of the neighborhood. But he adapted well, broadening his circle of friends, and expanding his interests. As always, he was academically gifted. He also learned to play the trombone, got braces, and began to question some of what he was being taught.

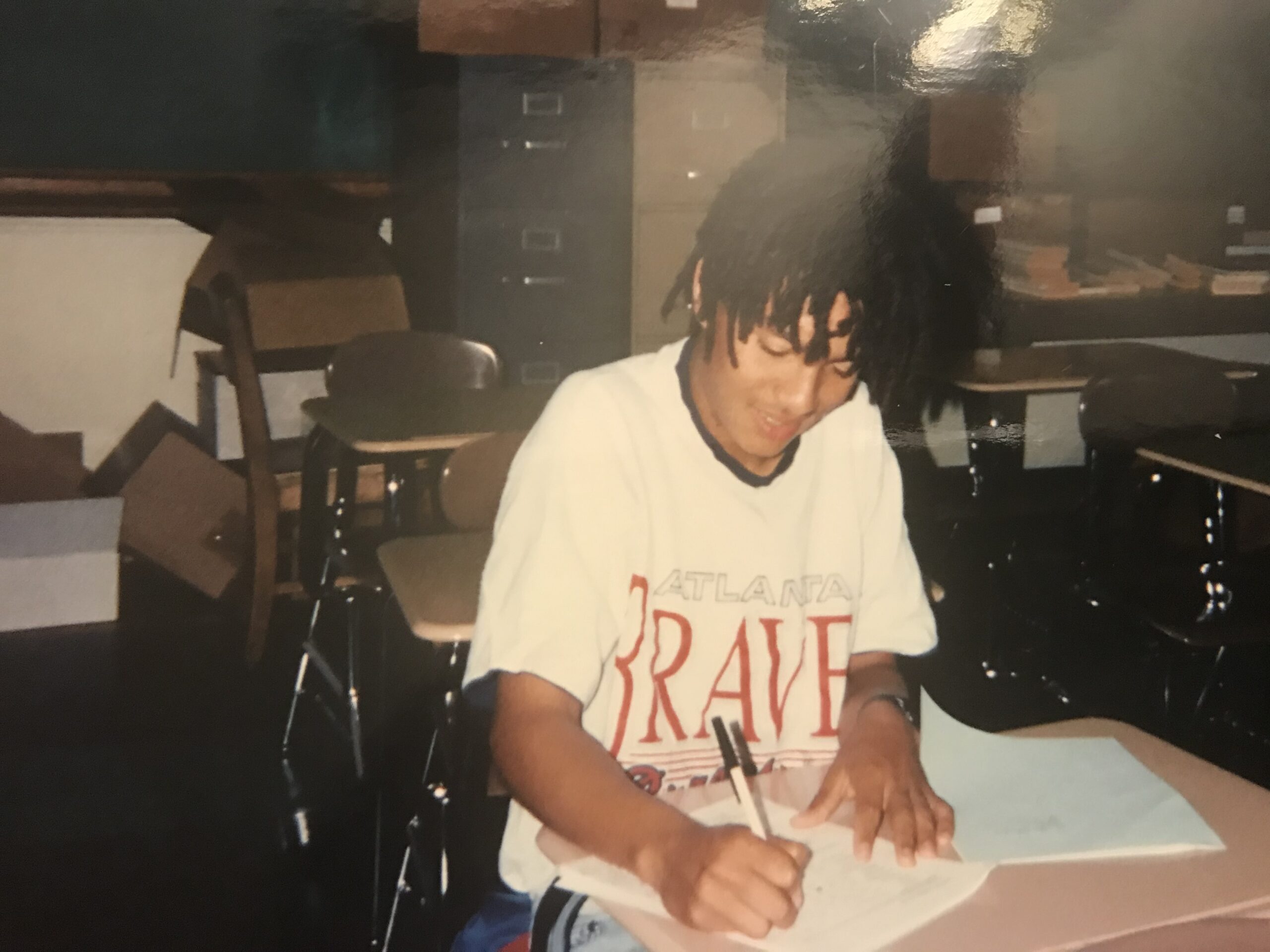

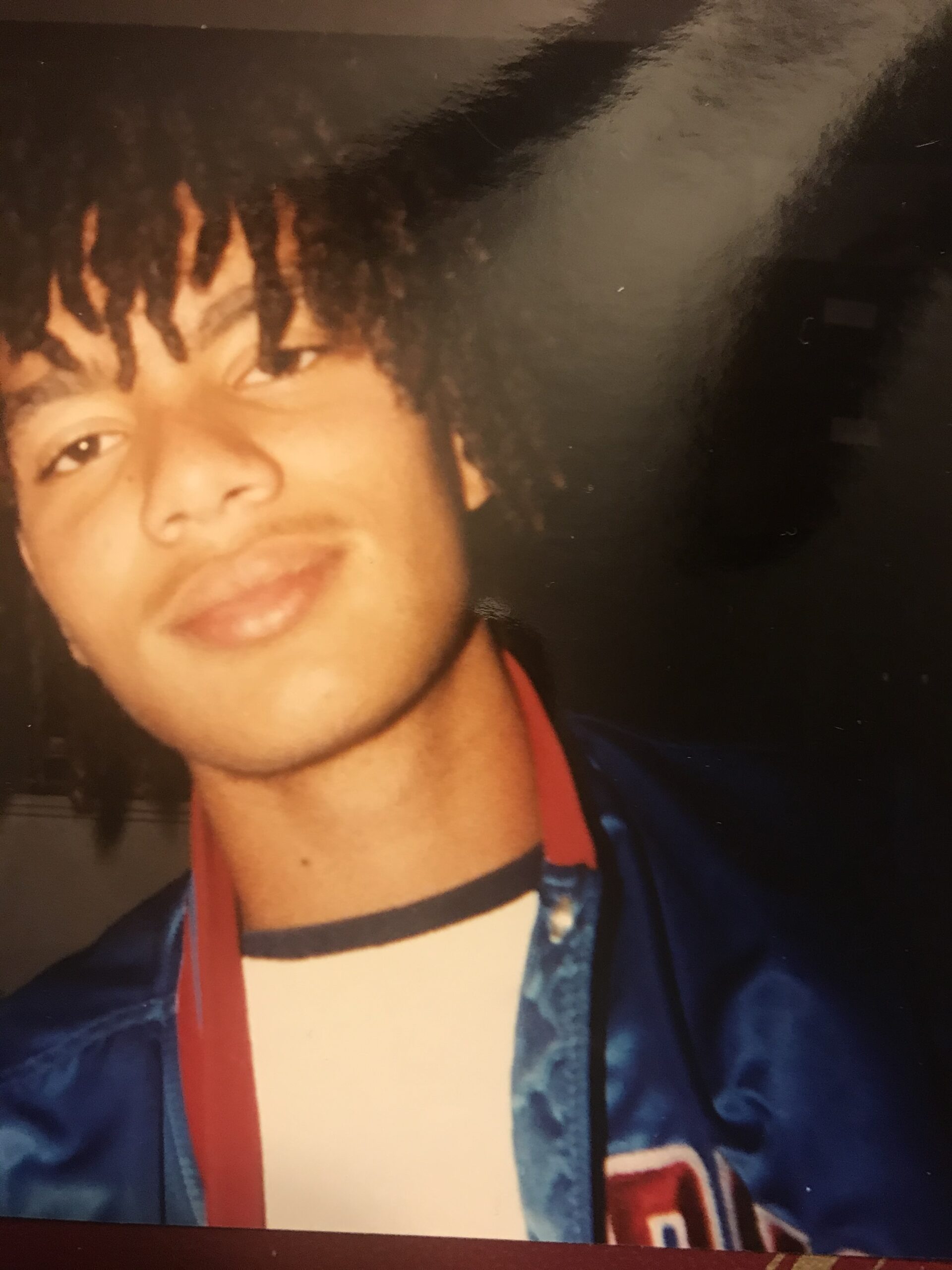

High School – Finding His Place and His Voice

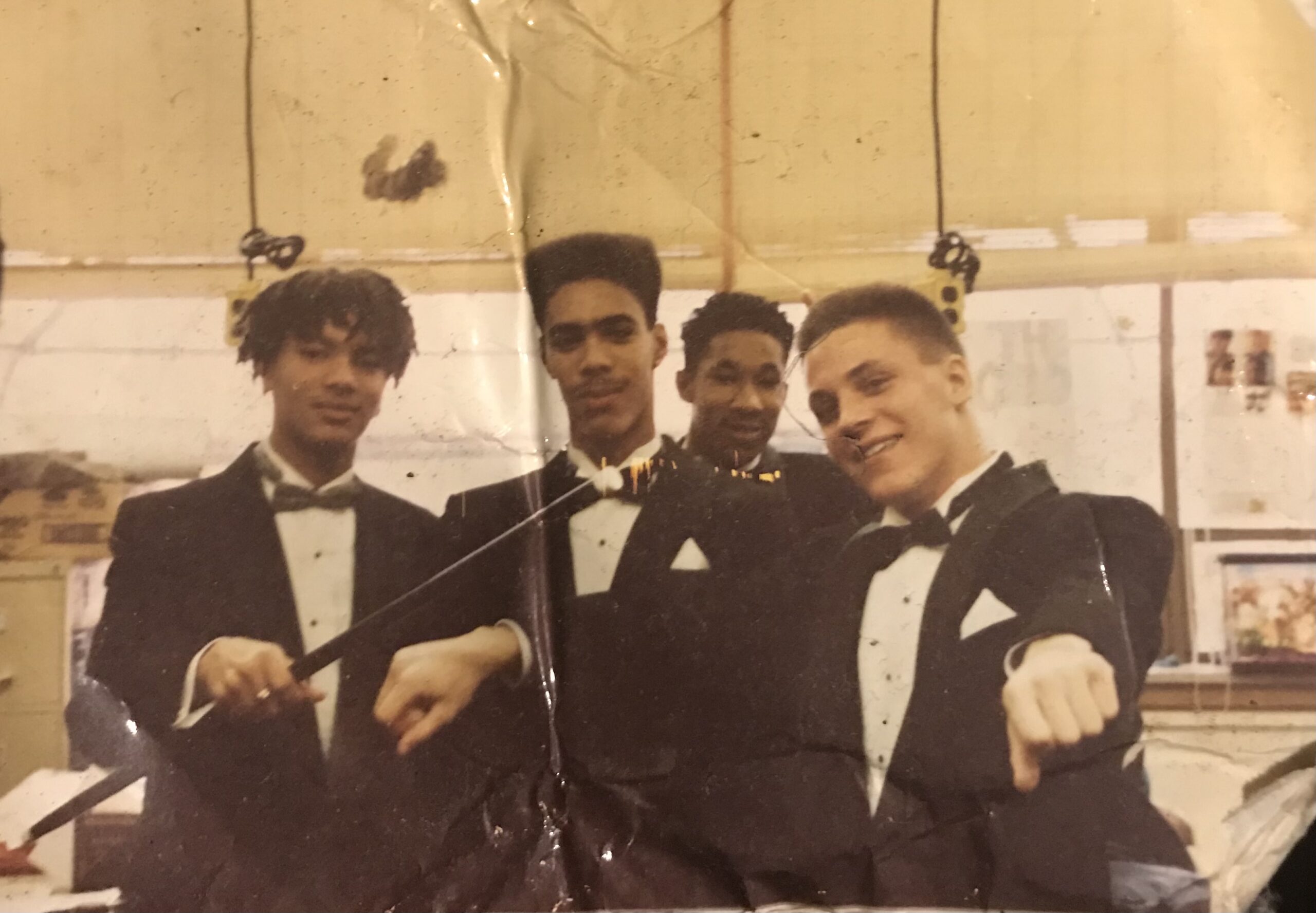

High School was a bit of a shock to the system. If middle school seemed big, high school was enormous and engendered feelings of anonymity and isolation. At times, Thomas seemed lonely, lost in the sea of new faces and personalities. But he soon found his place – and his voice. He joined the Marching Band, which wasn’t cool, but he liked playing the trombone, so why not? He also joined the Jazz Band, which was a lot cooler, more intimate, more in line with his tastes. And he found a whole new circle of friends when he signed up to work behind the scenes in the Theater Department. He loved doing that work, and it probably didn’t hurt that most of his fellow theater nerds were girls, many of whom continued to be close, intimate friends until the end of his life.

In the midst of all this, we became American citizens. Thomas and Catherine were minors, of course, so they didn’t have to go through the vetting process required of adult immigrants seeking citizenship. But the truth is I wasn’t nearly as vigorously vetted as were other, more “typical” immigrants. I believe my conversations with Thomas and Catherine about my privileged treatment started to solidify within Thomas his skepticism about equality in this country and some of the historical fairy tales that were being fed to students in school. For example, he was threatened with suspension when he challenged a History teacher (a HISTORY teacher!) who claimed that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery and that the enslaved were lucky to have been rescued from a life of poverty in Africa and given jobs and a place to live in America. In another instance, he was permanently kicked out of a class for his refusal to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance. I found out about this only a few years ago and asked him why he hadn’t mentioned it at the time, as he knew I would have supported him 100%. He said he took pity on the teacher and wanted to spare him the inevitable wrath that would have rained down on him. I have to admit I felt a little cheated, but I appreciated his compassion for the ignorant oaf.

Thomas lettered in two varsity sports – soccer and tennis – and did extremely well academically, particularly in math, so he was courted by several colleges, offering him full rides in their engineering schools. The last two schools on the list were the University of Michigan and Michigan State. Although U of M was considered the more prestigious of the two, Thomas was a diehard MSU sports fan and really couldn’t imagine attending the hated U of M. But we took the tour anyway – a private tour, led by a young woman of mixed race – like Thomas. At the end of the tour, she asked what his overall impression was, to which he said, “My overall impression is that it’s very White here.” She seemed taken aback, but the best she could come up with in response was, “Well, I’m sure you could find a club or something where you’d feel comfortable.” We both fought the urge to burst out laughing, thanked her for her time, and he chose MSU.

MSU – Finding His Path and Facing Tragedy

Thomas started at MSU in the Fall of 1993 with the intention of enrolling in the College of Engineering. Somewhere along the way, in his first semester, he had an epiphany. He had been told his entire life – and he bought into it – that as a Person of Color with mad math skills, he could become an engineer and write his own ticket anywhere in the country. But then he realized, with a little help from a friend, Vicente, a revolutionary Chilean rapper whom the universe placed in Thomas’s dorm freshman year, that he really wasn’t interested in engineering or in the wealth that could come from it. He decided instead to become a teacher and switched his major to math and history. Finally, he was on the path he was destined for.

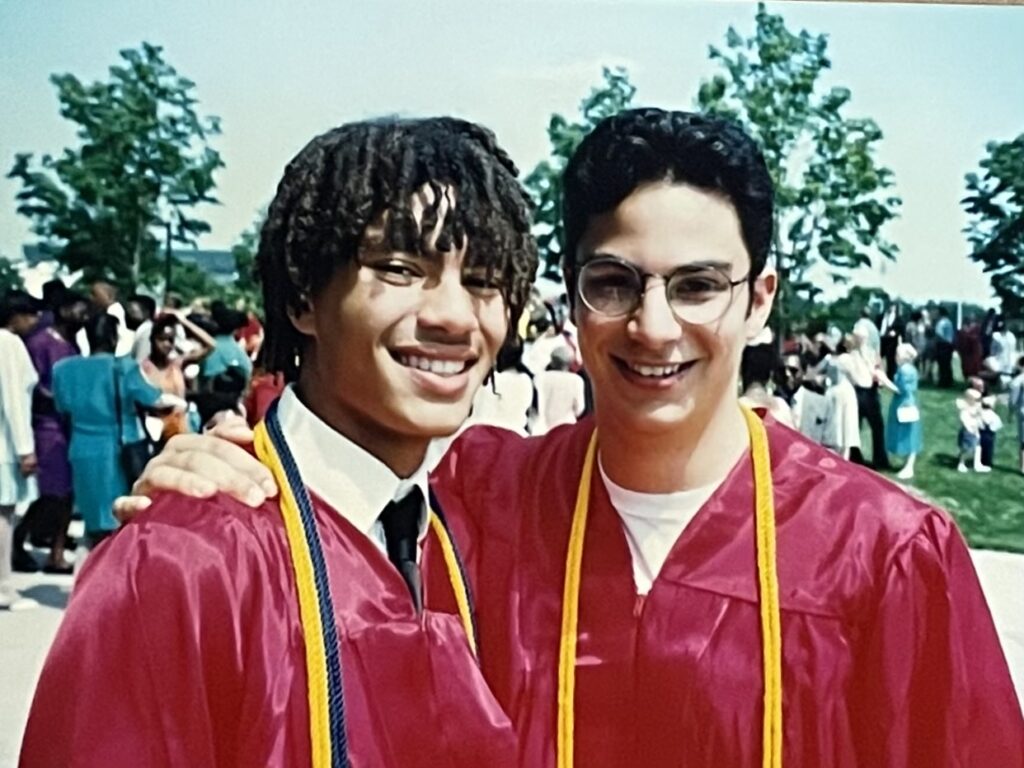

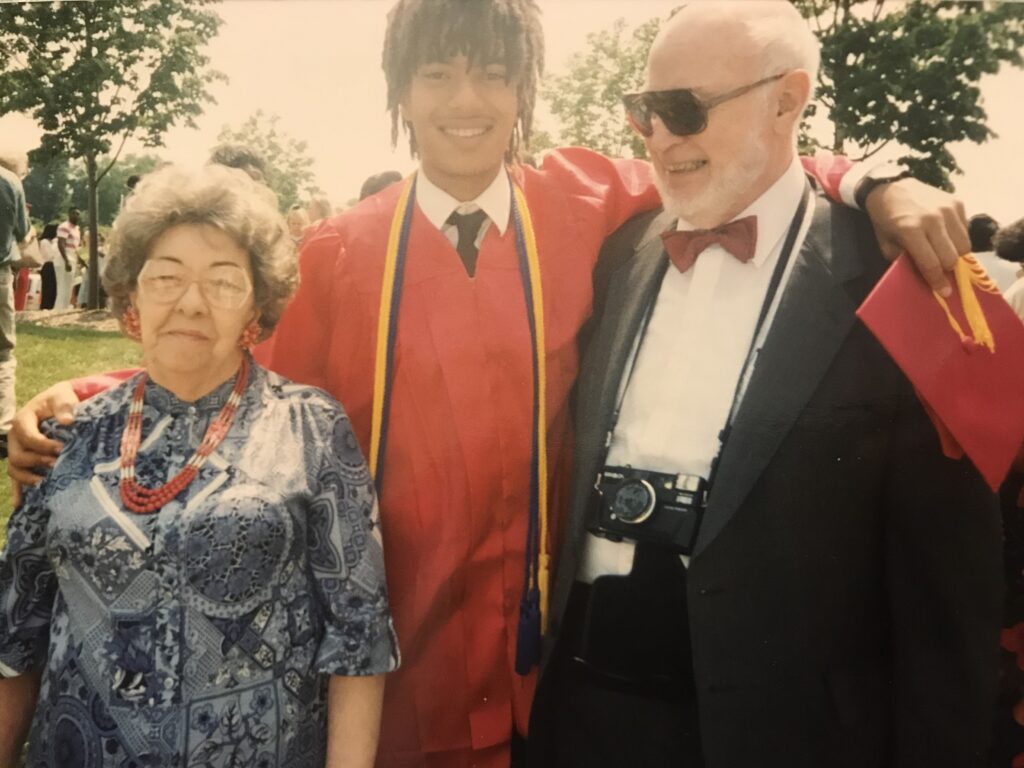

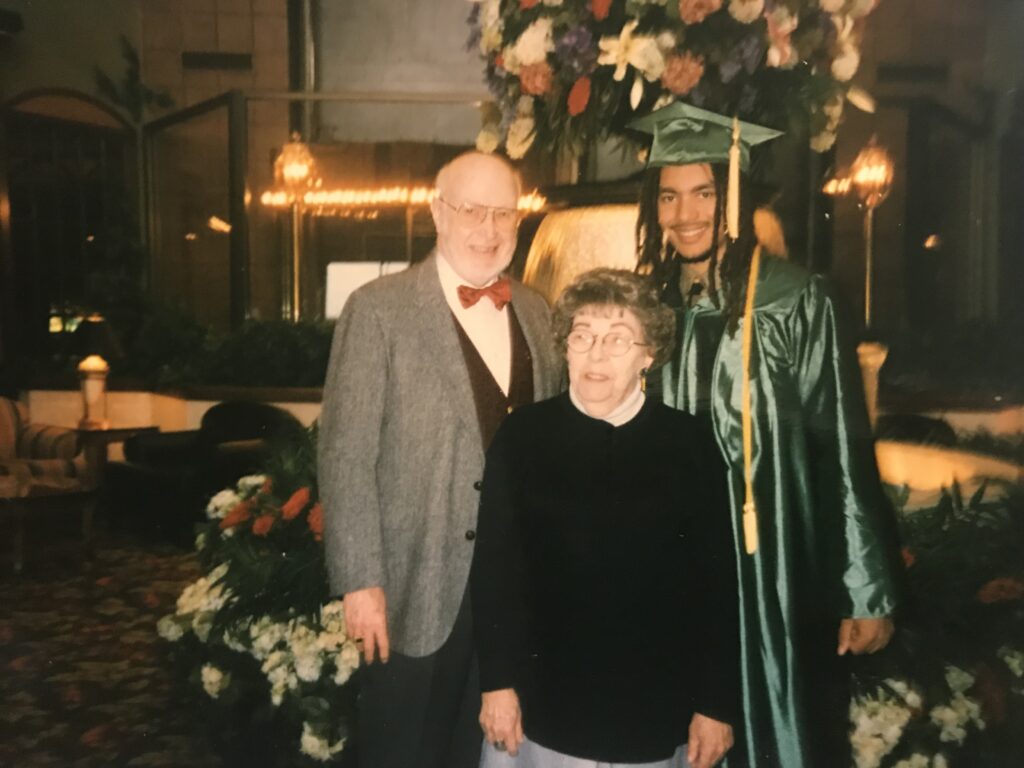

Thomas graduated with high honor in 1998 with a Math/History degree and a teaching certificate. He had landed a job in Baltimore and was in the final stages of preparing to move across the country when tragedy struck. His beloved grandparents – Grandma Honey and Grandpa Jack – died unexpectedly within about 2 weeks of each other. He was crushed. They had played such a key role in his life and were there for his graduation, beaming with pride, and now they were both gone. As their lives ended, his was just beginning. I told him the best way to honor them was to go to Baltimore and be the best teacher he could be. And he did.

Baltimore, Marriage, and the Peace Corps

Thomas began his teaching career at City College High School, a Baltimore public school. The school had sent recruiters to the Michigan State School of Education job fair who were smart enough to notice Thomas, invite him to sit down for an interview, and offer him a job on the spot. In the early days at the school, he was often mistaken for a student and threatened with detention for being in the hall without a pass. He was known for refusing to use the math textbook, and often lamented that the most academically “successful” students still insisted on carrying that gigantic book to class each day until nearly January, when they finally realized he was serious. One student who believed him immediately was Paul Atkinson. Paul went on to become a math teacher at City himself, and later the supervisor of the math department. Paul also happens to be the son of Jay Gillen, who became a dear mentor and friend who eventually brought Thomas into organizing with the Baltimore Algebra Project.

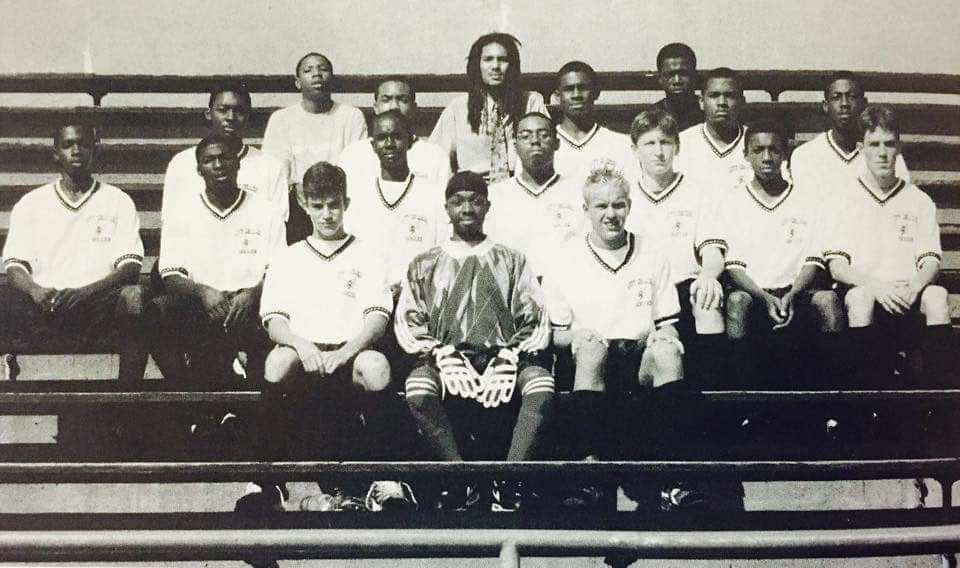

In addition to teaching math, Thomas (aka Coach Nik) organized a soccer team in an area where soccer wasn’t exactly a favorite – or known – sport. One of the kids on the City High School team that T coached, Sedrick Smith, is now the coach of the girls team at City. They just won their ninth straight championship this year.

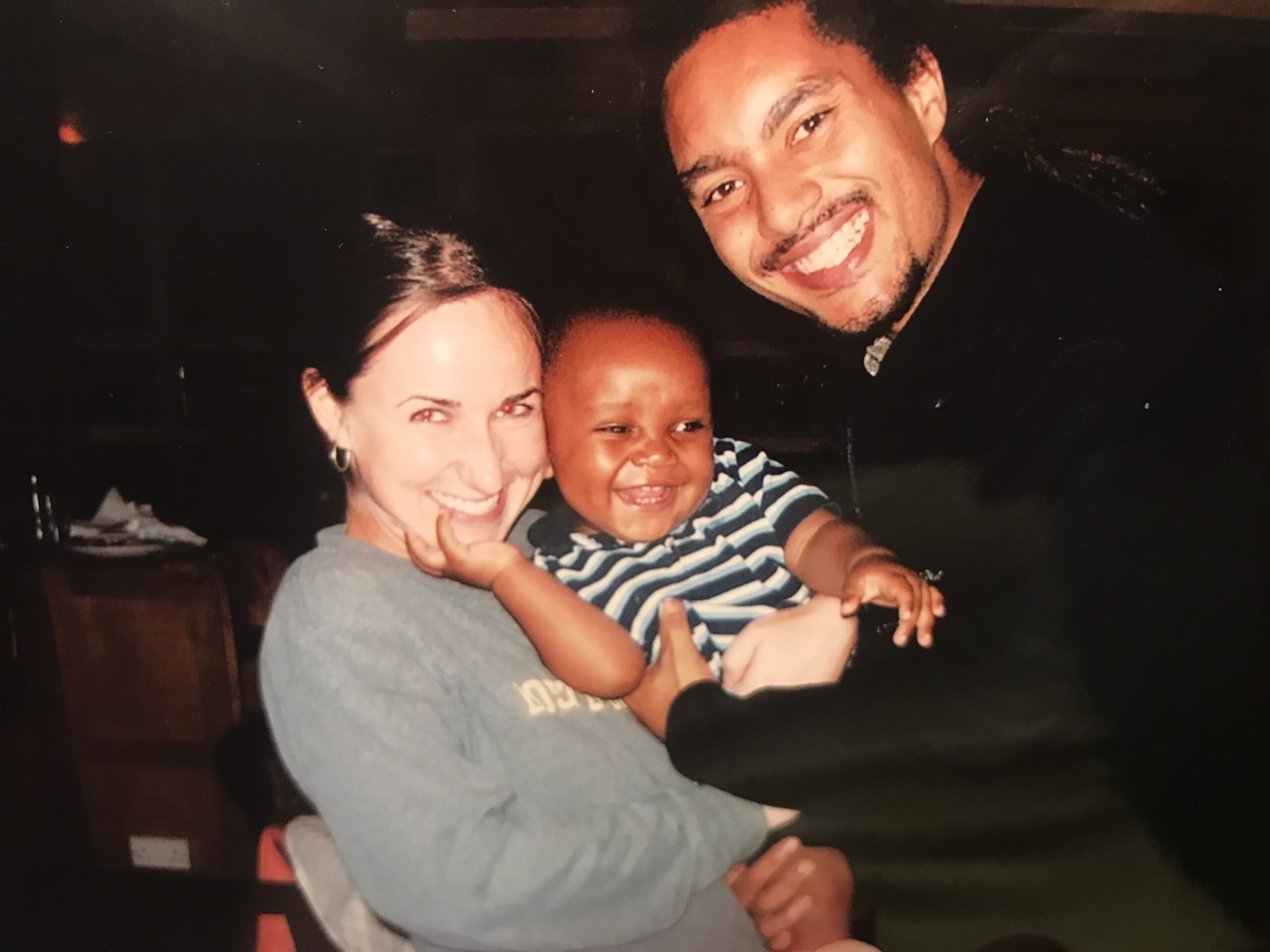

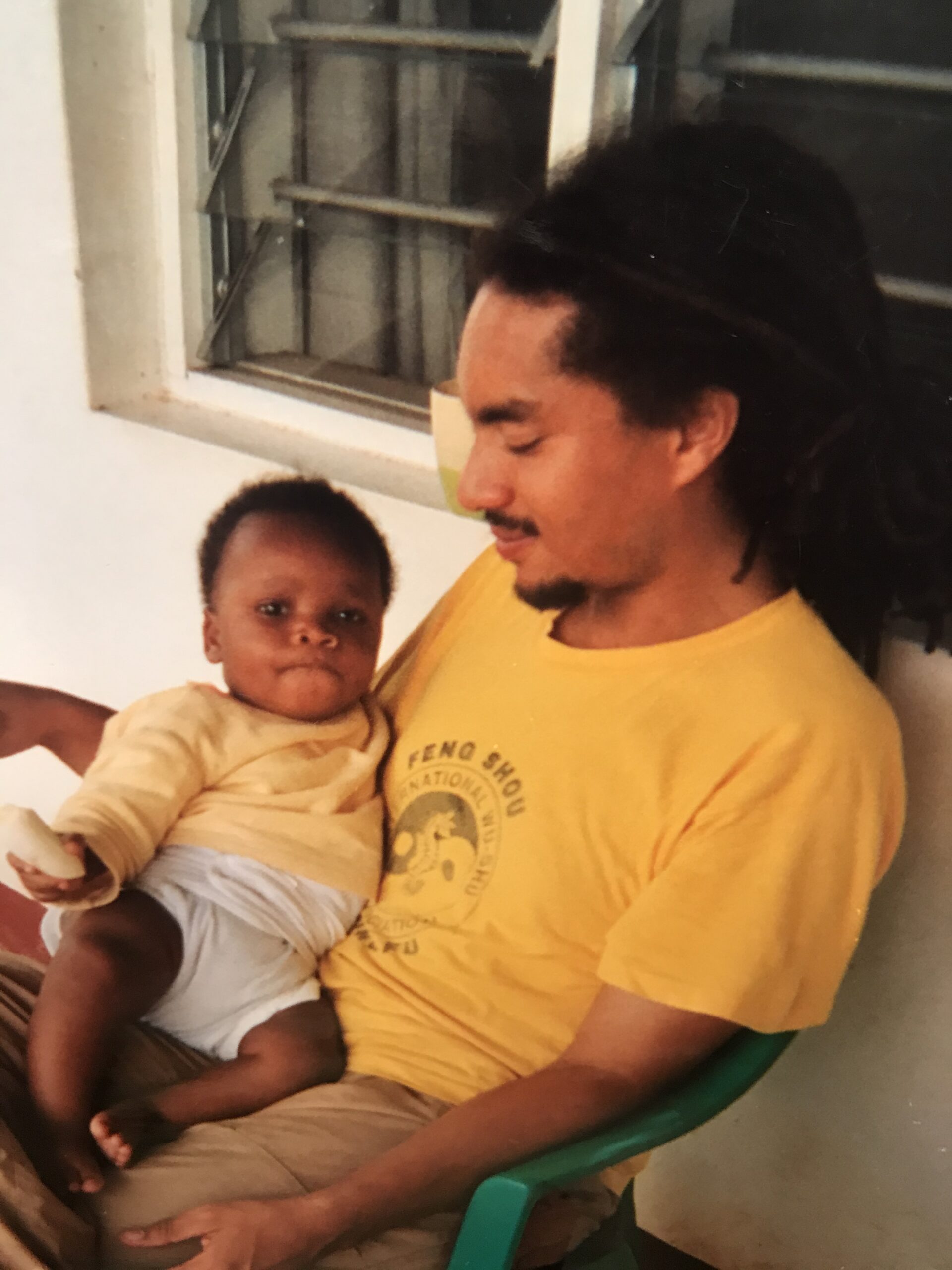

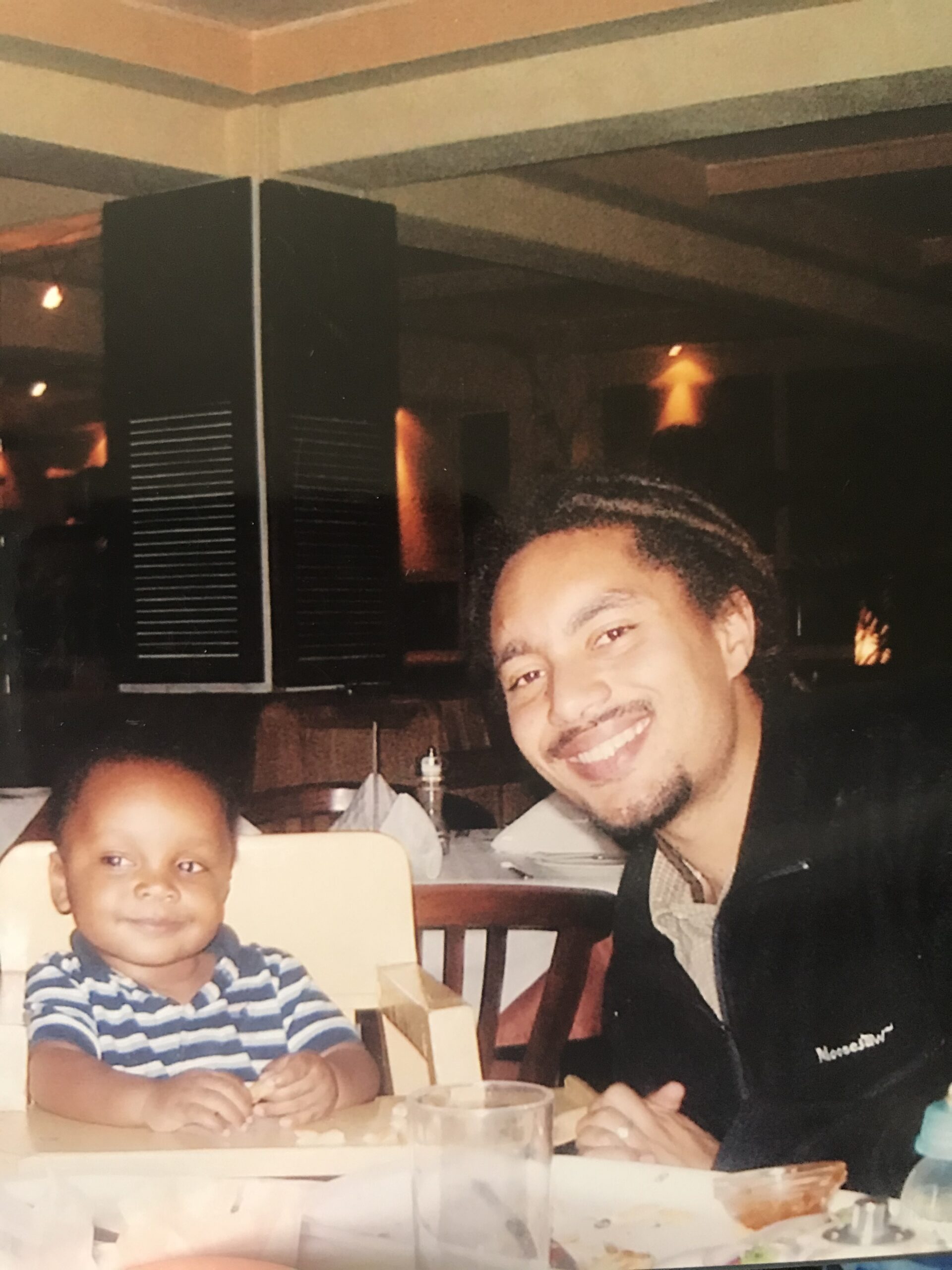

In 2000, Thomas and Michelle Tasch, whom he met playing co-ed rec soccer in college, were married at – where else? – the MSU chapel. It was a cold, snowy December night, but it was a lovely ceremony and reception attended by tons of family and friends. Thomas and Michelle returned to Baltimore, but began thinking there was more they could offer, so they applied to become Peace Corps volunteers. Eventually, they were accepted and were assigned to Masaka, Uganda, where Michelle, a nurse, worked in an orphanage, and Thomas served as a teacher trainer. Although they knew serving in the Peace Corps would change their lives for the better, they hadn’t anticipated one change that would enrich them in ways beyond belief. They adopted a baby boy, whom they called Izaac, whose mother had died shortly after his birth, and whose father was ill and unable to adequately care for him. The adoption process was frustrating and difficult, but ultimately, they prevailed, and Izaac became a cherished member of the family. When their period of service was up, the threesome returned to Baltimore.

Upon returning, the family was reunited with the Gillens. While at City before the Peace Corps, Thomas had become familiar with the work of Civil Rights icon and creator of the Algebra Project, Robert Moses, a man he came to revere. Bob’s book, Radical Equations, remained one of the most influential texts of Thomas’s entire life. With Jay’s mentorship, Thomas became a Math Literacy Youth Organizer with the Baltimore Algebra Project, a student-run organization with a dual purpose: tutoring students in math and engendering political activism at the grassroots level. His work with the BAP was life-changing, fundamentally solidifying his belief that youth asserting their own power is itself education as liberation. The experience set him further along the path that would define his life’s work, and he became deeply curious about the power and possibilities of grassroots youth and community organizing.

The Harvard Years and The Best Thing to Come from Cambridge

In 2006, T’s curiosities led him to doctoral studies, wanting the time and freedom to read deeply and widely at the intersections of education and the Black freedom struggle. His compelling application and near-perfect GRE score won him acceptance to every doctoral program he applied to, and he gave most serious consideration to the University of Wisconsin – Madison before Harvard lured him with a prestigious Presidential Fellowship. He and I (Carla) became friends on day one when we were placed in the same small group for the absurd array of team-building activities we were required to complete. T often recalled the memory of how he (at his size), had to trust me (at my size), with some version of a trust fall. He looked me up and down, worried, but upon noticing his hesitation, I quickly reassured him, with a carefully placed F-bomb that communicated my general mood during these activities, that I could handle it. That sealed the friendship.

Thomas was a coveted teaching assistant in countless courses – from statistics and economics, to urban education and qualitative research methods – and served as co-chair of the editorial board of the Harvard Educational Review during the years in which we published a special issue celebrating the inauguration of Barack Obama and a book on Humanizing Education.

Thomas quickly learned that Harvard is hardly the place to study freedom. The education he received largely came from a small community of like-minded peers who worked to create parallel spaces for critical study of radical thought, as well as through his participation and leadership in protests of the school’s pitiful treatment of anything having to do with race and justice. His relationships with these scholar-activist colleagues and a handful of professors – including those involved in a doctoral research practicum on community organizing that published A Match on Dry Grass – became his lifeline throughout his doctoral study.

Eventually, well over a decade later, T finished checking off all the boxes required for the doctorate. He wrote an absolutely stunning dissertation – rich, powerful portraits of X, Wayne, Chris, and Comrade – four of the young men with whom he had worked in his time with the Baltimore Algebra Project. His deep, abiding love and reverence for these young people is evident on each of the 200+ pages.

T never bothered to pick up his degree or attend graduation. His experience of doctoral studies was in keeping with W.E.B. DuBois’s reflections on his own time there: “The honor, I assure you, was all Harvard’s.”

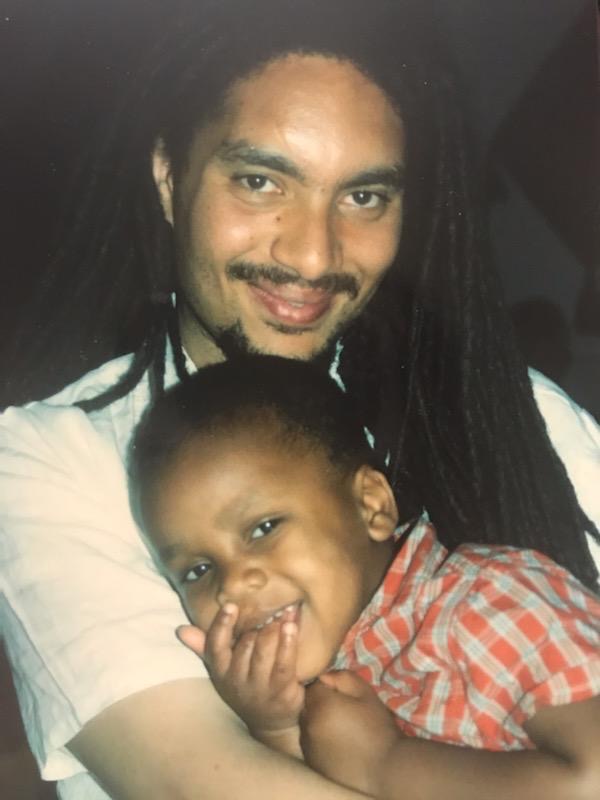

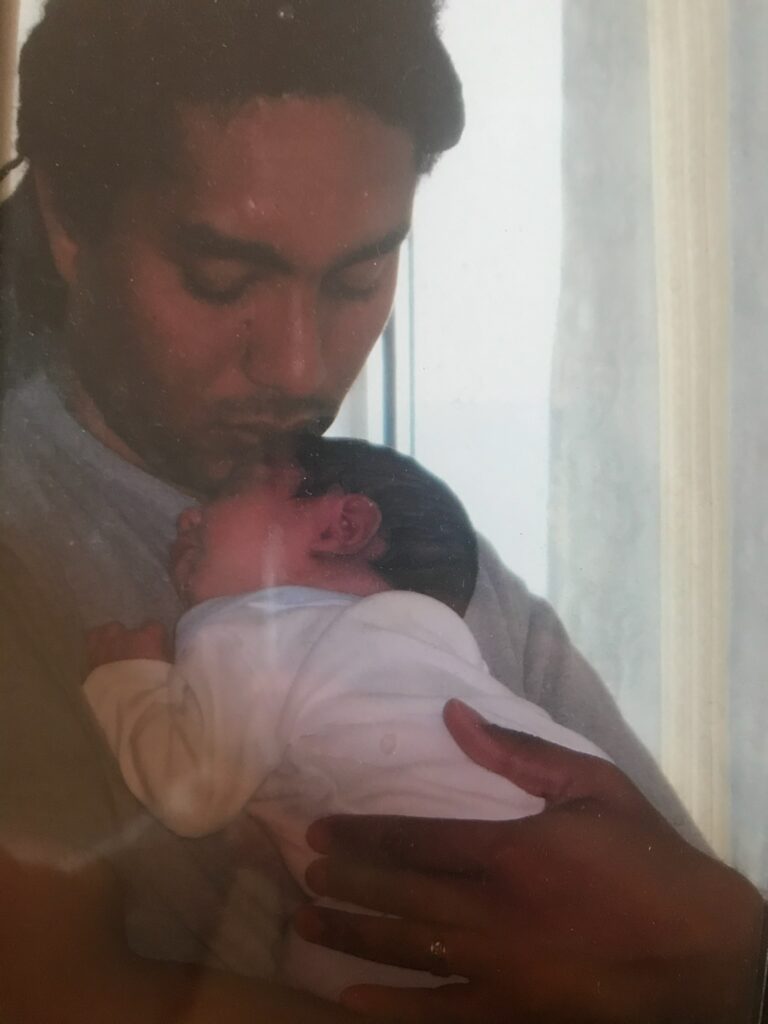

Though there is much T was happy to leave behind in Cambridge, the place also holds countless treasured memories. The best gift to come from Cambridge, of course, is Akenna William Nikundiwe, born July 7, 2008 at 3:03 p.m., after torturing Michelle for 12+ hours of labor and then requiring delivery by C-section. I can’t think of Gutman Library without remembering T calming Akenna, during meetings on the upper levels, by holding him near the windows so he could watch the tops of the swaying trees and take in the light. Akenna can’t remember his time at Harvard, but the rest of us certainly do.

Homecomings and Homegoing

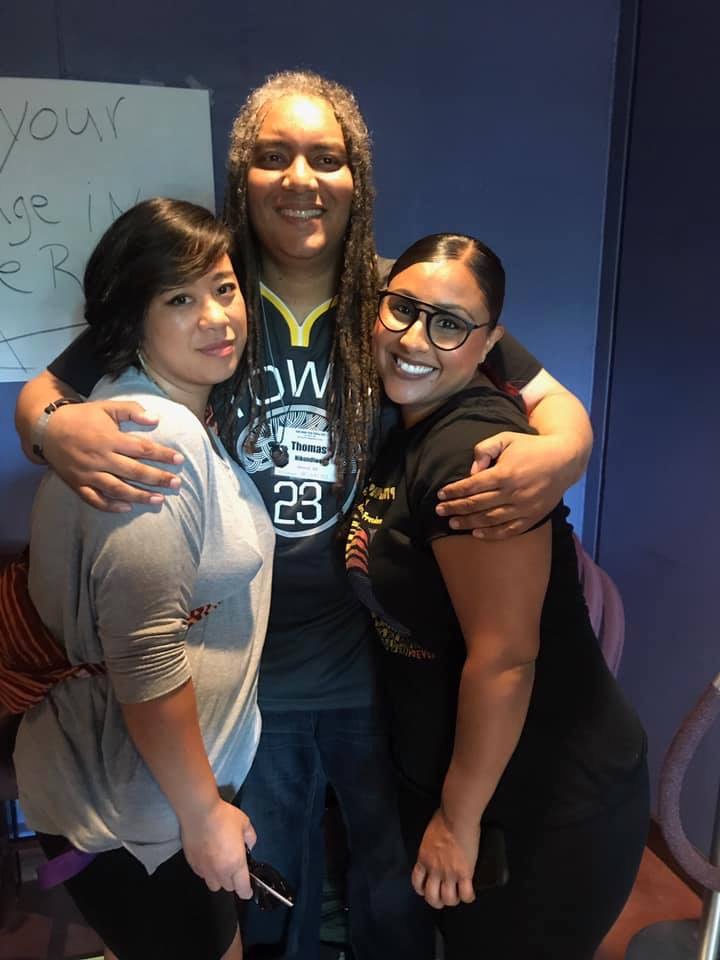

When Tara Mack, the founding executive director of the Education for Liberation Network, was transitioning out of the role, Thomas, having served on the board of the organization since its inception, applied to continue her work stewarding the network. The Education for Liberation Network, which brings together youth, activists, organizers, educators, and artists who share a commitment to education as the practice of freedom, supports the possibility of a national movement for education justice by connecting people to people, people to knowledge, and people to resources. For Thomas, directing the network was the ideal way to take up his place in struggle. He never thought of it as a job. He understood it as a medium through which he could advance education justice and the Black freedom struggle by building relationships and connections between and among youth and educators fighting for freedom. These relationships, he believed, were a chance to practice education for liberation.

Leading the Education for Liberation Network was a homecoming, of sorts, returning Thomas to the spirit of his work with the Baltimore Algebra Project – where he was happiest – and to the kinds of commitments and work that preceded Harvard and have always been his true calling and passion. This season of life brought other homecomings, too. Thomas and Michelle decided to say goodbye to Boston and head back to Michigan. After an amicable split in which they remained extraordinary co-parents and one of each other’s best friends, they wanted to be closer to extended family and all the support that family provides. They settled two new households: one filled with pets, the other with video games. I’m sure it’s not hard to guess which was which.

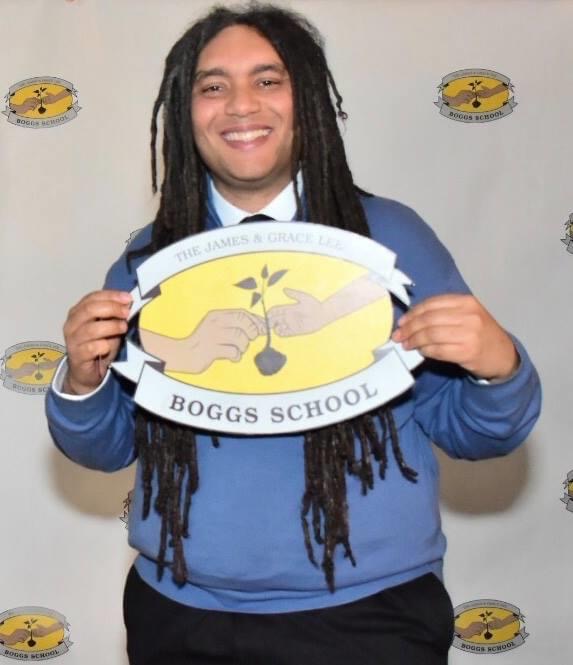

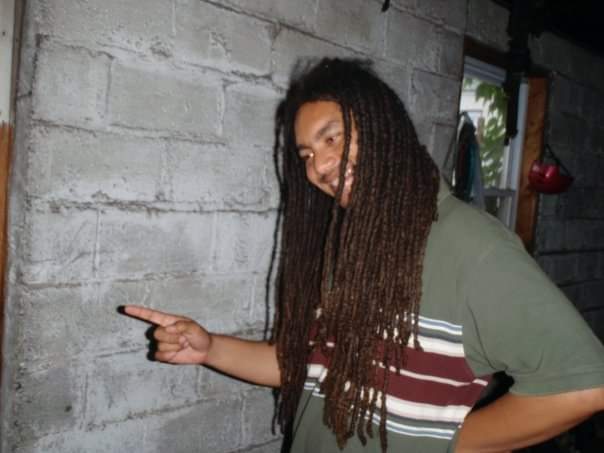

T truly made home in Detroit, where he remained for the last 12 years of his life, reuniting with friends from childhood and college while also growing new branches of his beloved Michigan community. He intentionally rooted himself and his work, in the spirit of Jimmy and Grace Lee Boggs, in a deep dedication to growing Detroit’s soul. Akenna will graduate this year from the James and Grace Lee Boggs School, where Thomas proudly served as a Board member.

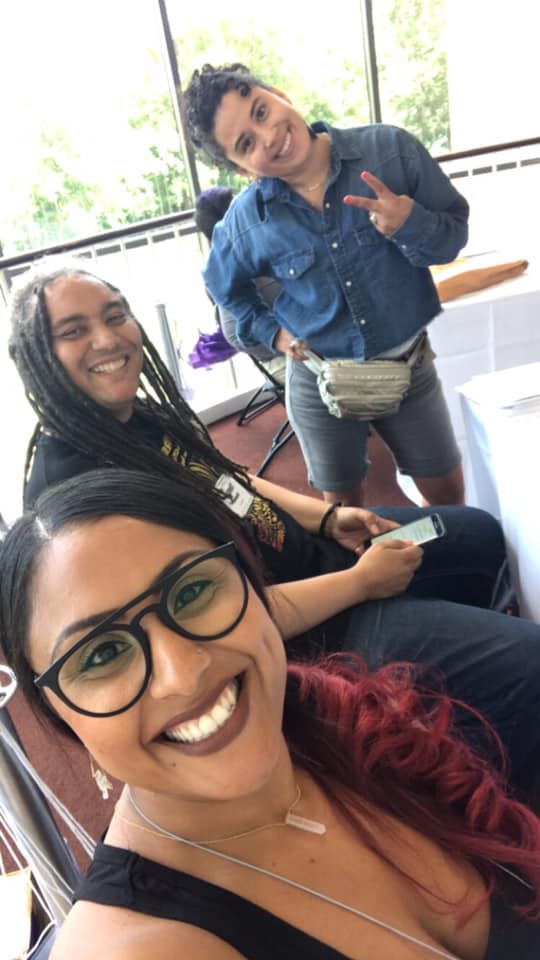

I joined him in his commitment to Detroit a couple of years later. Realizing that we hated being apart, T and I decided to be together, and I moved from the east coast to be with him and the boys. Later, we bought our house in Rosedale Park, a Detroit neighborhood that we feel deeply connected to. Transitioning him out of his original home here, barely a mile away, I rode in the back of the U-Haul holding the giant basketball hoop steady, after a long argument over how to get it from Point A to Point B. Once that hoop found its way onto our new driveway, the house made its first gesture toward becoming home for T. Since then, this already 100 year-old house has held us through it all – holidays and celebrations, COVID and cancer. It bursts with Thomas’s presence and holds the memories of our precious and beautiful life together in every old corner, nook, and cranny.

The house also held Thomas in his final homegoing on July 4, 2021. Just as he wished, he died in our home with as much peace, dignity, and overflowing love as one can hope for. However short his life, however painful and cruel its ending, it was so fully lived and he was so fully loved. There is no way to capture such a life in writing. His life is best expressed through the ways in which we – this beloved community he left behind – continue to love and care for each other, remember and tell his stories, and struggle together for freedom and for a world worthy of our children.

Did You Know…?

Share a Photo

Please share any photos you’d like the community to see of Thomas, or photos that Thomas’s memory brings to mind.